Providing suburban mass transit at minimal cost

The biggest problem with American suburban transportation networks is they effectively serve only one mode of transportation: cars. Unfortunately, this happens to be the loudest, least efficient, most expensive, most space-consuming, most dangerous, most polluting, highest-maintenance form of transportation.

Even if we disregard safety, accessibility, environmental impact, noise, and public health, and we only care about traffic, we would still be overwhelmingly in favor of public transit, since it’s many times better at moving people.

Rail networks work well, but they require expensive infrastructure which many cities don’t have, especially suburbs. The initial cost of a rail network in most suburbs, complete with stations, would be prohibitive, and space would have to be carved out for the rails. A bus network, however, uses assets every suburb already has: roads and buses! With a little initiative and dedication, almost any American suburb could have a first-class bus system in place within a year.

A dedicated bus lane can move many more people per hour than a car lane. The only problem is there’s little incentive for individuals to take a bus, because on an individual level, buses are slower than cars. Buses get stuck in traffic like everything else. The result is a version of the prisoner’s dilemma. A dedicated bus lane eliminates that problem and provides a reason to ride the bus: No traffic!

Yes, buses work in the United States! Nearly every American city already has a bus system. They’re called school buses. If they work for students, they can work for everyone. If students are worth public transportation, so is everyone.

Every city and its public school district should work together to create a public bus system which serves all residents, students and non-students alike. Every public school district already has a fleet of buses, and they go unused most of the day. By combining resources, school districts would reduce costs thanks to the city chipping in, and the city would have a comprehensive bus system at a fraction of the cost it would take to build one from scratch.

Case Study: Plano, TX

As an example, let's examine how such a bike network would work in Plano, TX, a typical American suburb, located in the Dallas metro area. Plano is known for its good public schools and middle-to-upper-middle-class demographics. Nearly all Plano residents live in a single-family home and drive every time they leave the house.

High schools only (at first)

First, we would begin this system by only combining the public system with high school routes. Elementary and middle school buses and routes would remain unchanged.

Nearly all of Plano ISD’s high schools are located adjacent to a divided arterial road. This should make it easy to serve them with a public bus system; simply run buses along our major roads and make every high school one of the stops.

Eventually, PISD and Plano should also bring the local community college (Collin College) into the fold, as well as the nearby suburbs of Allen, McKinney, Frisco, and their school districts. Due to economies of scale, a county-wide bus system would only be increasingly efficient and cost-effective as more entities get involved.

Routes

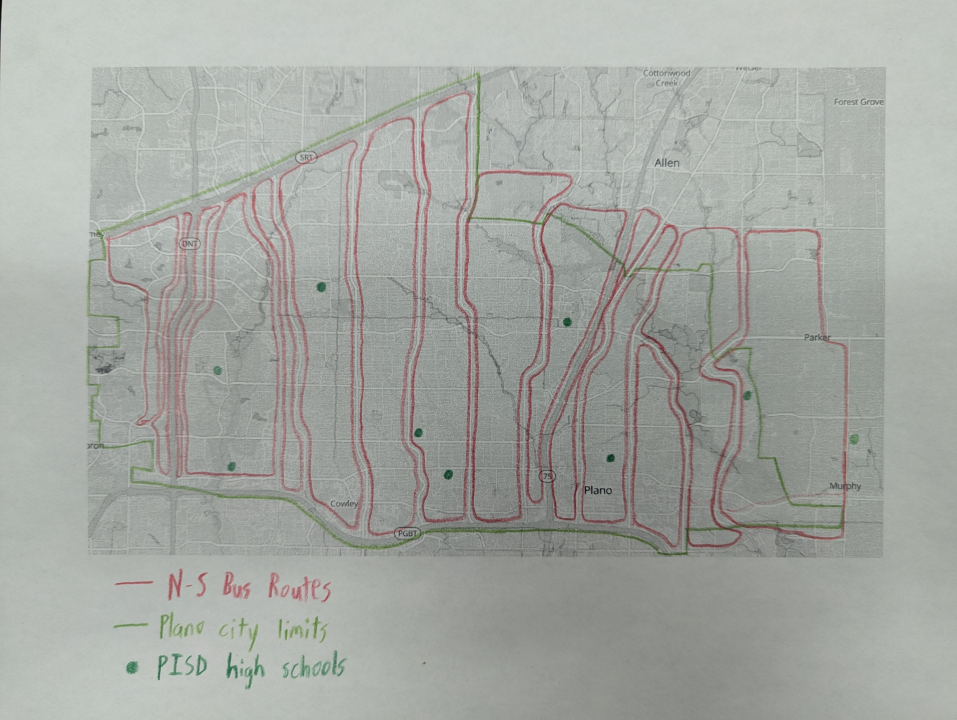

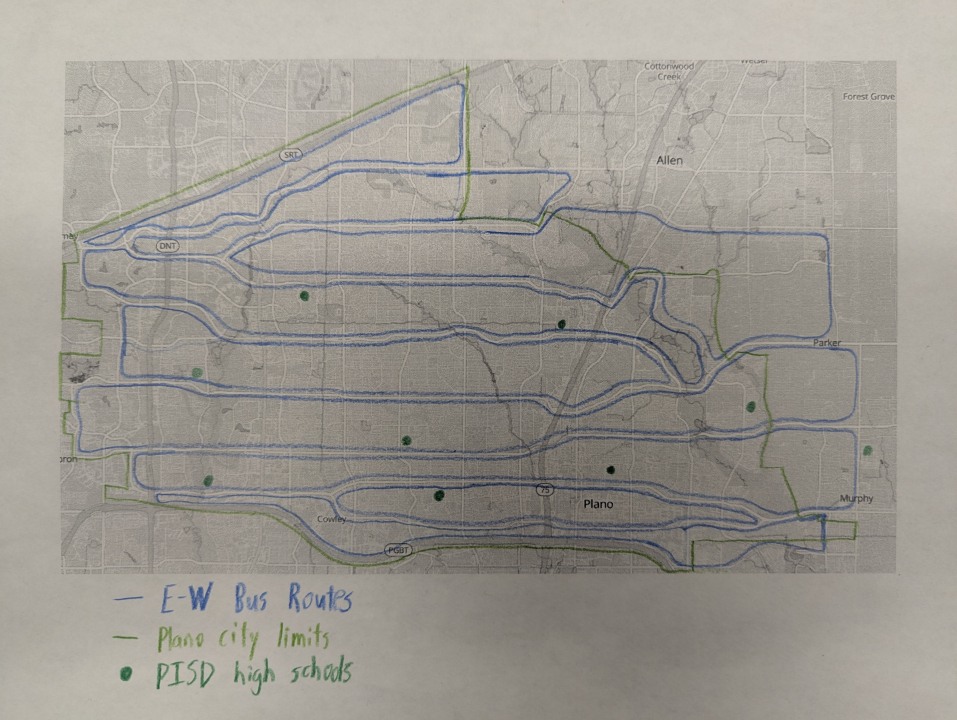

Designing the routes themselves is easy, since Plano’s roads are in a grid pattern. Every route would run primarily either east-west or north-south on major roads, completing a long skinny loop which spans the entire length of town.

In the provided (admittedly primitive, hand-drawn) images, all loops run clockwise, which means most buses only ever make right turns. This not only helps buses move faster, but makes it easier for traffic to flow around them.

All major roads in Plano would be served by a bus moving in both directions, and in order to get from any part of Plano to another, it should only be necessary to take a maximum of two buses: one which runs north-south, and another which runs east-west. No one will need to learn the routes since they’re essentially the same as a city map, and ideally, buses come often enough that no one needs to know the schedule either.

As an example, let’s use the goal of each stop being served by a bus every 15 minutes. If we assume buses move one mile every three minutes, buses would need to be spaced five miles apart. A loop 20 total miles in length (most would be shorter) would need four buses to reach our goal, and if there are 20 such loops (likely less), it would take at most 80 buses to create a citywide system that covers every major road and arrives on 15-minute intervals. Plano ISD already has four times that number of buses.

Buses

Initially, any city could simply use existing school buses, but as older buses leave service, they can be replaced with city-type buses and slowly convert the fleet in that manner. Ideally, these buses would be hybrid engines, or even entirely electric, which would cut down on noise while improving air quality. Over the lifetime of the bus, the savings in fuel makes hybrids cheaper than diesel engines.

The new buses should also come with bike racks on the front so people can ride to the bus stop, get on, and ride off. By integrating buses with another mode of transportation (bikes), accessibility is further improved, and the “reach” of the bus system is extended; a stop may be outside of comfortable walking distance, but easily within biking distance. All bus stops should also have a bike rack.

Safety

Some parents may be concerned with having their kids share the bus with adults, which is another reason it would be wise to pilot this program with high schools only; they’re nearly adults already and are generally less vulnerable.

Sharing the bus with adults will keep students safer. For one thing, students riding public buses is a standard practice in nearly every non-American country, and adult-on-student violence on buses isn’t a problem. What already happens on public school buses is a problem. Kids bully other kids, harass other kids, and beat up other kids, largely because there are no adults around to stop them. In the presence of adults, students are more likely to behave.

Student performance and attendance

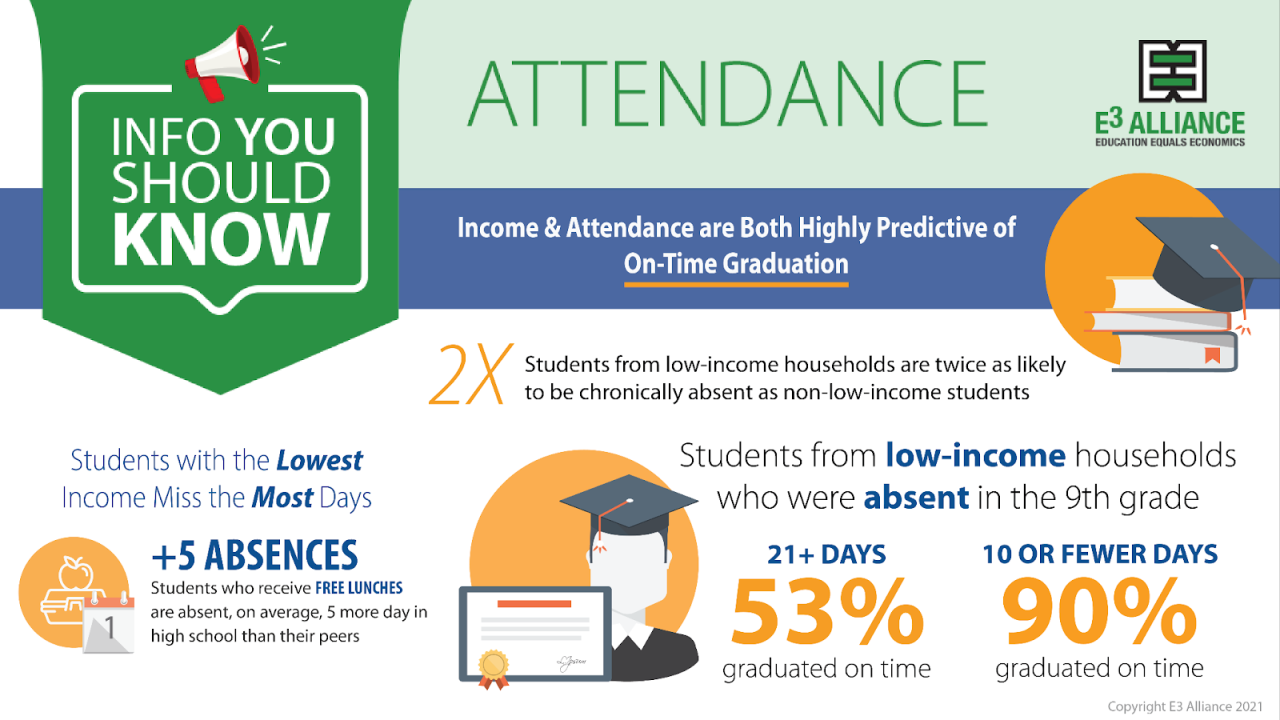

One of the least-talked-about problems with typical school bus systems is inflexibility and the effect that has on students who rely on the bus. Almost without exception, the students with the greatest discipline problems and those most at-risk of failing to graduate are students who participate in zero sports, clubs, and after-school activities. Students who take the bus are essentially unable to join any of these things, because the bus doesn’t pick up after band practice. They also can’t come in early or stay late to get help in tutorials.

This turns into a triple-whammy when you consider bus-dependent students are more likely to be economically disadvantaged and have parents who frequently aren’t at home. A student who already has both of these disadvantages, can’t get academic help before or after school, and is prevented from being a part of the school community is playing against a stacked deck. We need to do a better job of providing equal opportunity for these students.

Furthermore, a comprehensive bus system solves truancy issues. As it currently stands, if a student misses the bus, they have no means of getting to school. If instead the bus comes every 15 minutes, they simply take the next bus. As a result, what was a full day of absence is now only five minutes late to 1st period. With higher attendance numbers and graduation rates, state funding will improve. This alone will help the buses pay for themselves.