Distant

Before starting a long-distance hike or bike tour, a lot of preparation is done. Where to go. How to get there. What to bring. Getting in shape. For some, this is a process which, off-and-on, can take over a year. This time though, I feel like I’ve barely prepared at all. I’ve never taken such a nonchalant approach to a grand adventure.

The average household contains over 300,000 objects. The average hiker/biker carries fewer than 100, and lives that way for potentially months at a time. This summer, I’ll have only 54 items, including the bike itself, each individual bag strapped to it, and the clothes on my back. In extreme cases, bringing the wrong things can literally be a matter of life and death.

Those 50-100 items must be chosen carefully; it’s absolutely essential to bring everything you need, while ideally carrying nothing you don’t. Every ounce must be worth the effort of you pulling its weight. As a result, a lot of thought goes into a packing list.

Because I’ve done this kind of thing before, it’s become easy to make a packing list. My over-analytical tendencies have resulted in an impressive spreadsheet of all my packing lists, detailing the weights and other measurable quantities of every item I have or have ever used. This is, of course, organized by category, ascending weight, and in the case of bike tours, which bag the item was in.

At this point, all I have to do is pick a previous hike/bike trip, copy-paste the entire sheet, and make a few tweaks here and there. Maybe I’m bringing one or two extra articles of clothing since I’m going somewhere colder, or in the opposite case, I’m leaving a few items off the list. But 90% of the work is done before I even begin.

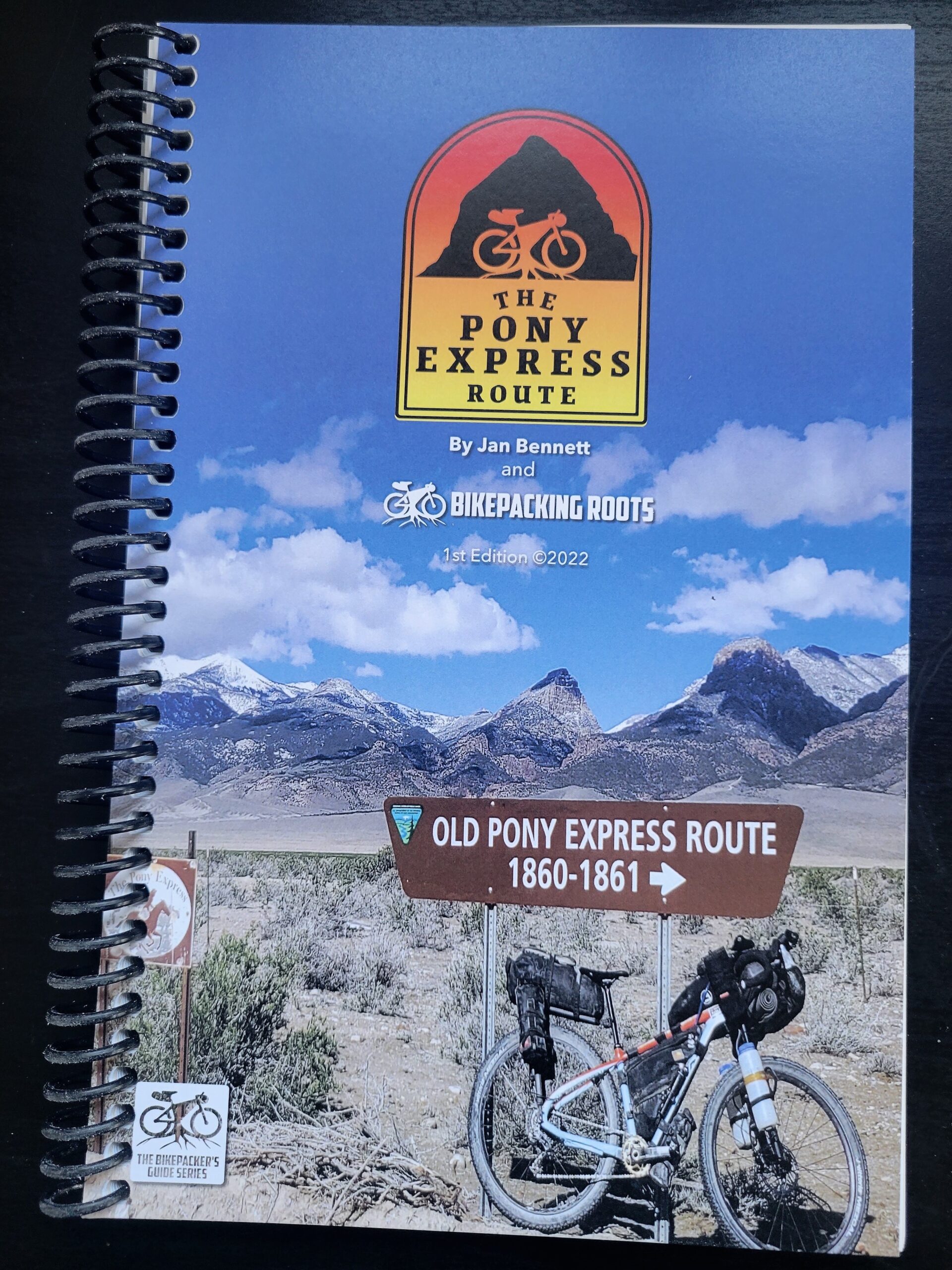

Increasingly, I’ve been hiking/biking established trails and routes, like the TransAmerica Bike Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail, and soon, the Pony Express Bikepacking Route. In the past, I’d pick a destination and figure out how to get there. Because of this change, I don’t even need to plot a route anymore, nor figure out where I’ll need to buy supplies, and sometimes I don’t even need to find places to stay; all those things have already been worked out and are often neatly organized in a guidebook.

Similarly, I haven’t been training for this ride the way I normally would. I can’t tell exactly why. It’s possible the lack of needed preparation in other facets has overtaken my entire mentality with an overwhelming drift toward “I’ll be fine.” Or maybe I’ve realized I don’t necessarily need to over-prepare; it’s not a race. Maybe teaching the equivalent of three college-level physics courses, all of them for the first time, developing every bit from scratch, has left me with little free time with which to train. Maybe I’m less inclined to go for a ride when it’s not as fun as it was in Hill Country. Or maybe I’ve just gotten lazy.

I’d thought about spending an extra week training, after the end of the school year and before hitting the trail. But I’ve thought better of it. Again, it’s not a race. However, day 1 is possibly the most difficult day of the entire ride. From Sacramento to South Lake Tahoe, over 200 km (125 miles), almost entirely uphill, and a good chunk of it will be on singletrack. At this point, I’m worried about whether or not I’ll even make it to Tahoe before nightfall.

Historically, Pony Express riders attempted to make the entire trek in ten 10 days. The fastest recorded time was only a week. My most optimistic goal is three weeks, which still comes to over 160 km/day (100 miles/day), considerably faster than I’ve ever bike toured, even on pavement. Achieving this goal will take a ton of guts and a metric tonne of tailwind.

June

June