Gear Prep

As I’m a numbers guy, and a little over-analytical, I have a tendency to think about my gear a lot. When you’re hiking or biking all day, you have a lot of time to think anyway, and when your mind’s not on food, it’s often on your gear. You start to wish you’d brought certain things, or that you’d left other things behind, or you wish you had something else. After a while, you start mentally putting together a better packing list for your next trip.

One of the things hikers and bikers worry about most is the weight of their gear. Generally speaking, the lighter the better. There are two ways to accomplish this:

- Get the most advanced, high-tech gear available

- Bring less stuff

The lightest-weight people do a combination of both, but #2 goes a lot farther than #1. Even if all your gear is ultralight, you’re not going ultralight if you bring a ton of stuff. But you can get away with carrying very little if you’re smart about what you bring, and manage to bring only a few things that, when used in different ways or in combination with each other, cover your needs for all scenarios.

Someone more clever than me once said, “You can either hike comfortably, or you can camp comfortably. It’s hard to do both.” There’s a lot of truth in that.

Folks on the AT seems to fall into the “Camp Comfortably” category. It’s not unusual to see packs of 65 L and up. When people saw me with my 50 L pack, a lot of the east coast crowd sneered, “You’re never making it to Maine with only that much gear,” as they covered half my daily mileage. When I asked one of these people why he needed so much stuff, his response was, “For comfort.” What on Earth is comfortable about a 20 kg pack??? Noticeably, as I got closer to Maine and only the strong were left, most of them had packs closer to my size.

From my experience hiking in the western states, a 50 L pack is considered normal. Out west was where the ultralight movement got going, and you see the influence even among those not necessarily trying to go ultralight. When folks out there see me with my typical pack, the most common response is, “Not bad! You could probably get even lighter if you wanted to.”

The ultimate goal is to strike a balance. Carry little enough that you’re hiking comfortably, but have enough that you camp comfortably as well. There’s no magic bullet for this, as it has a lot to do with some key knowledge: knowing what you’re willing to put up with. Some people don’t mind the cold, others don’t mind being wet, others can sleep on or in just about anything. If you know what you need to stay comfortable, and what you can do without, you can pare down your packing list without sacrificing much.

It also helps to talk to other hikers/bikers. Every time you go on a trip, you’ll learn another trick or a use for something you hadn’t thought of. Whenever I’m stopped and I see another hiker/biker, I immediately start checking out their setup and asking them about anything unusual I see. This is especially true for biking, because I haven’t yet found a bike shop that has an adequate knowledge of bike touring, nor enough gear intended for that purpose. As you learn more and more of these, you can leave more and more gear at home.

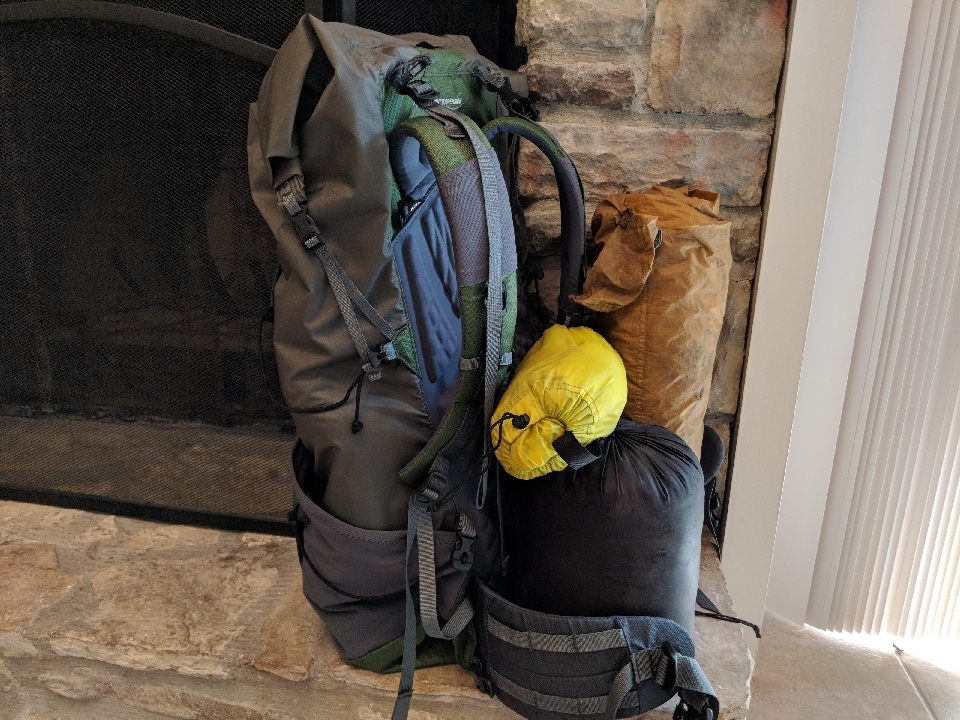

Compared to my AT thru-hike in 2015, I’m bringing a lot of the same gear, including the same sleeping bag and tent. The most noticeable change, by far, is the pack itself. The one I’ll be using for the PCT is 10 L larger in capacity, but only about 100 grams heavier. I still like my 50 L pack; I consider it an ideal size, and I don’t necessarily plan on carrying more gear on the PCT. The main reason for the larger pack is increased capacity for food and water. As detailed in a previous post, the PCT’s resupply points and water sources are much more spread-out, so being able to carry more is critical.

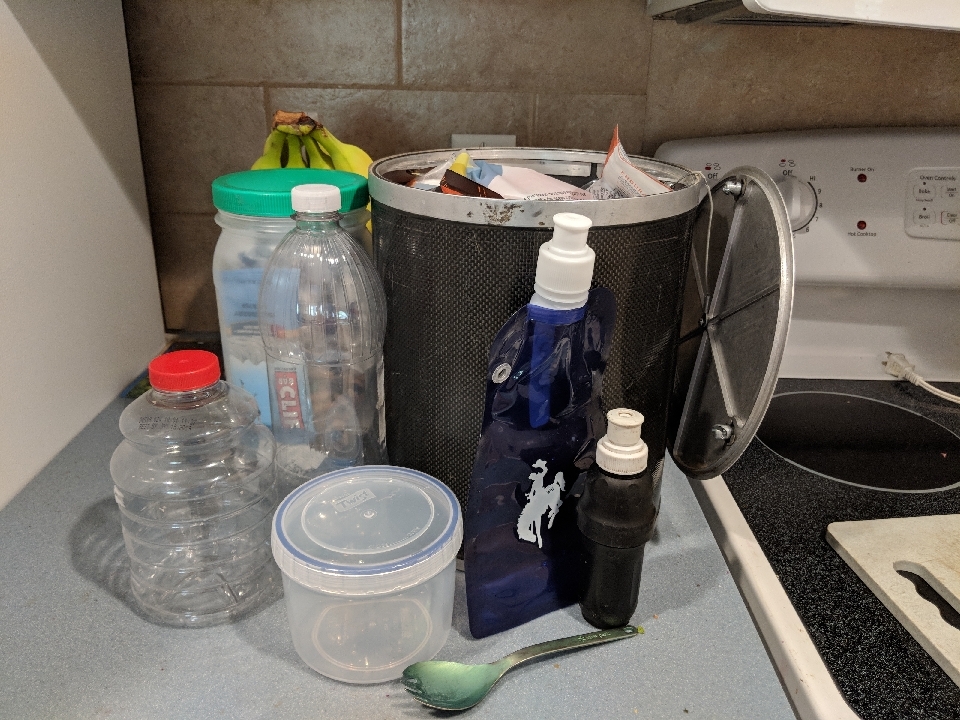

My skin-out base weight will be less than that on on the AT by roughly 1 kg, despite carrying what I consider to be more gear. As opposed to the AT, this time I’ll be carrying a fleece pullover and a pair of tights. About the only significant gear I’ve ditched is my campstove and sleeping bag liner. I find “cooked meals” on the trail no more satisfying than cold ones, and most things that can be easily cooked in a portable campstove can be constituted by soaking them in water. As for the sleeping bag liner, the additional clothes I’ll carry will more than make up for its warmth.

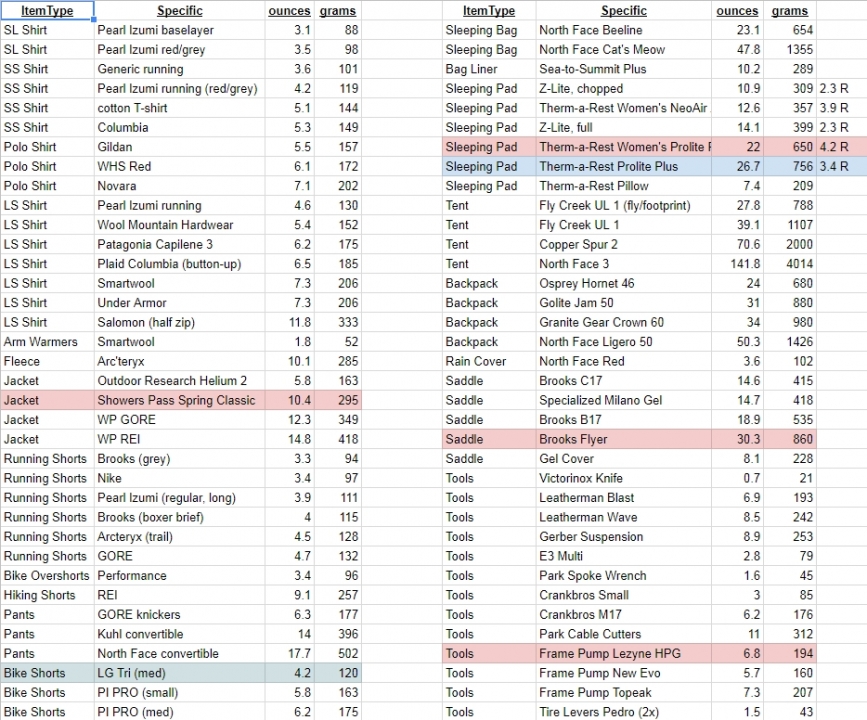

Part of what’s helped me pare down my weight is careful data collection and analysis. I’ve painstakingly made a spreadsheet cataloging the weight of every piece of gear I own (and a few I don't). Sometimes different combos of gear come out to much less than you imagine (two pairs of running shorts weigh less than one pair of hiking shorts!). Once you have the data, you can assemble several different theoretical packing lists and see what the total weight would be, or see the total effect of swapping one piece of gear for another. Doing this has made me realize what the real culprits are for heavy loads (especially bike gear), and after re-thinking the approach, it’s been possible to ditch more weight than I thought possible, all while sacrificing almost nothing.

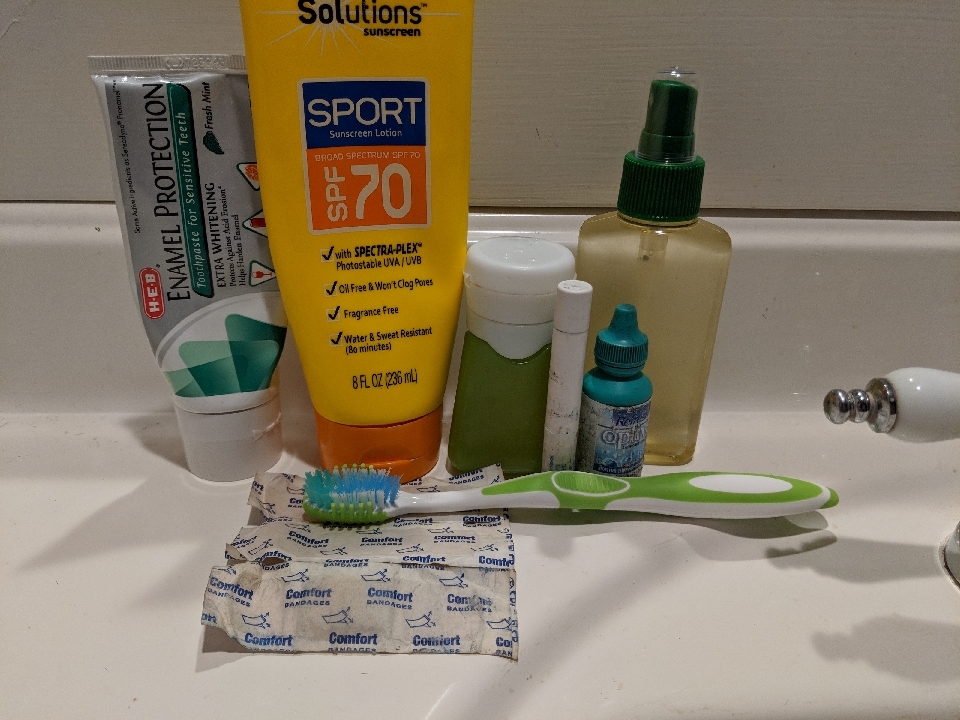

If you’re curious, check out my full packing list for this hike. With a little tweaking, a similar packing list would work well for almost any long-distance thru-hike.

June

June